Reports United's investigation exposes systemic law evasion and industry complicity

A recent Reporters United’s investigation into the illegal end-of-life sale of TRADER III — a tanker linked to companies of Greek shipowner and media magnate Vangelis Marinakis — lays bare how Europe’s most powerful shipping interests still funnel toxic end-of-life ships to Bangladesh’s tidal beaches. It also records, in the words of a senior Greek official, a policy of deliberate indifference that lets these illegal exports sail on.

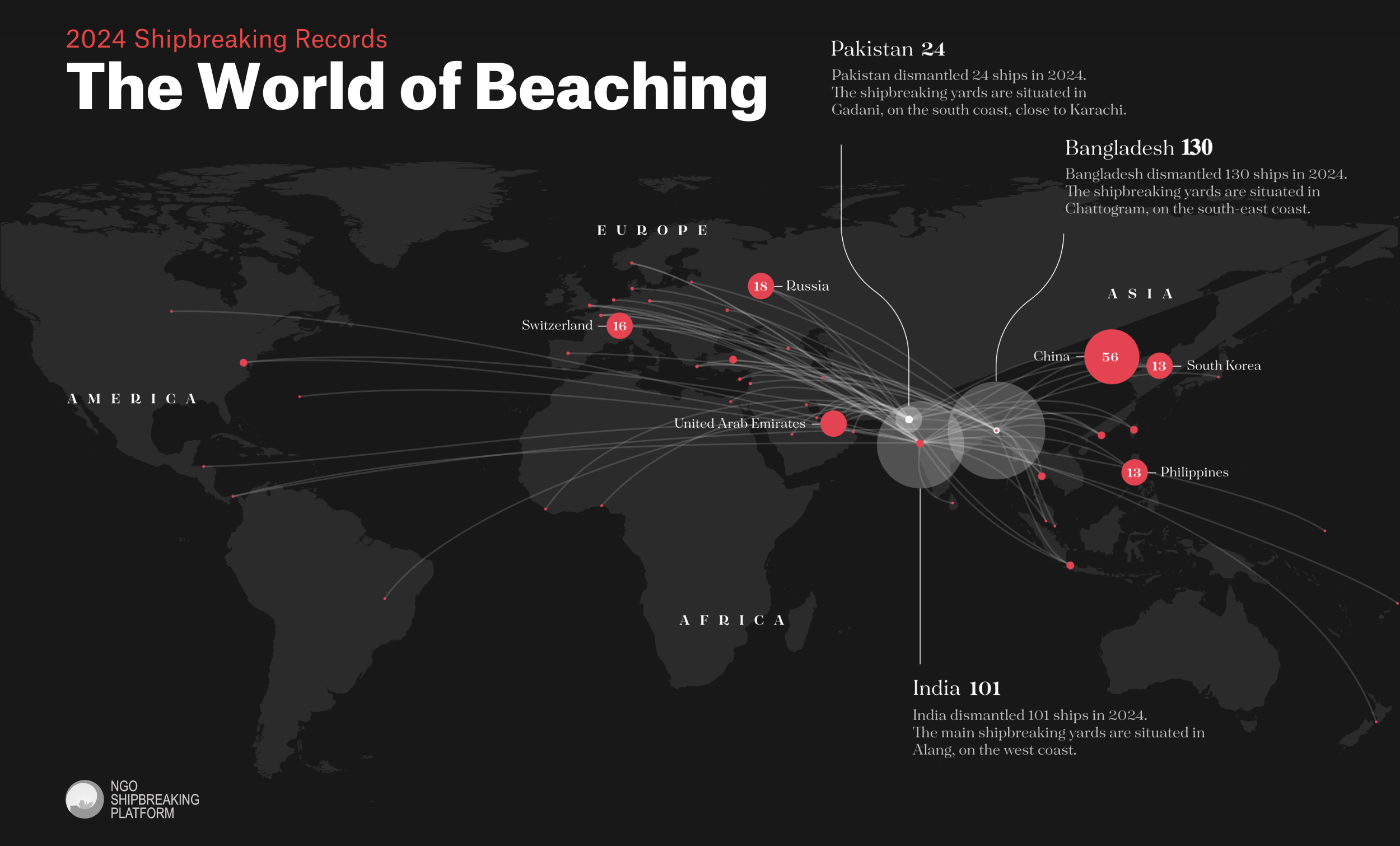

The facts are stark. On 29 January 2025 the TRADER III called port at Nemrut, Turkey. The next day it tracked toward Chios, cut south across Greek territorial waters, drifted off Egypt until 14 February, then headed east towards the shipbreaking beach of Chattogram, Bangladesh. On 15 March the tanker was beached at KR Ship Recycling Industries’ King Steel yard. By then, the deal chain had done what it was designed to do: deliver illegally a high-value hull to a non-OECD beach, far from EU oversight, for workers to cut it by hand amid hazardous substances onboard.

At the centre of the deal stands Global Marketing Systems (GMS), the world’s largest cash buyer of scrap ships — and a company long accused of enabling the world's toxic shipbreaking trade. The journalists document that Marinakis-linked interests sold the vessel directly to GMS. Scrap dealers, such as GMS, arbitrage lax standards and higher per-tonne prices paid by South Asian beaching yards.

The report also showcases how ship owners and GMS get away with trafficking ships to South Asian beaches. In June 2025, GMS hosted a webinar featuring Petros Varelidis, Greece’s Secretary-General for Natural Environment. There, Varelidis spelled out — without ambiguity — a policy of wilful non-enforcement when it comes to regulating exports of end-of-life ships like TRADER III from Greek waters. He also went further, dismissing EU officials responsible for monitoring ship recycling as “low-level bureaucrats”.

Inaction by Greek authorities causes harm. Chattogram's yards remain among the world’s deadliest work places. King Steel yard itself recorded an accident in August while the TRADER III was beached there. Europe’s legal framework is unambiguous: exports of end-of-life ships from the EU to non-OECD are banned, and the EU Ship Recycling Regulation channels EU-flag ships to approved yards — a list that does not include beaching yards in Bangladesh. Owners dodge this with flags of convenience and cash-buyer transfers, but courts across Europe have begun to pierce the veil of such deals, recognising owners’ duty of care to ensure sustainable ship recycling.

Greece and Turkey are the main European chokepoints — the last predictable places to stop on the way to a beaching yard. Yet, as Reporters United’s file shows, Greece “pretends”, and Turkey looks away, even when NGOs provide concrete case alerts. “Greek and Turkish authorities have a very bad track record of turning a blind eye,” our policy team told the reporters, reflecting years of unanswered warnings about illegal exports staged from their waters.