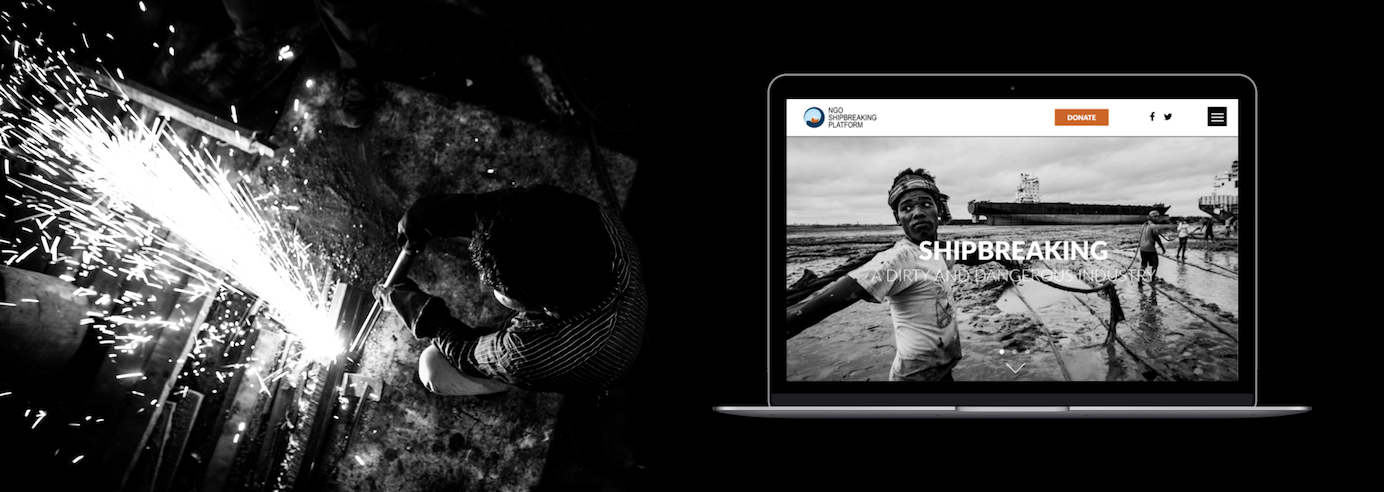

Record-breaking 90% of end-of-life tonnage scrapped on South Asian beaches

According to new data released today by the NGO Shipbreaking Platform, 744 large ocean-going commercial vessels were sold to the scrap yards in 2018. Of these vessels, 518 were broken down on tidal mudflats in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, amounting to a record-breaking 90,4% of the gross tonnage dismantled globally.

Last year, at least 35 workers lost their lives when breaking apart the global fleet. The Platform documented at least 14 workers that died in Alang, making 2018 one of one of the worse years for Indian yards in terms of accident records in the last decade. Another 20 workers died and 12 workers were severely injured in the Bangladeshi yards. In Pakistan, local sources confirmed 1 death and 27 injuries. Seven injuries were linked to yet another fire that broke out on-board a beached tanker.

DUMPERS 2018 – Worst practices

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES, GREECE and UNITED STATES OF AMERICA top the list of country dumpers in 2018. UAE owners were responsible for the highest absolute number of ships sold to South Asian shipbreaking yards in 2018: there were 61 ships in total. Greek owners, beached 57 vessels out of a total of 66 sold for demolition. American owners closely followed with 53 end-of-life vessels broken up on South Asian tidal mudflats.

The ‘worst corporate dumper’ prize goes to the South Korean liner Sinokor Merchant Marine. The company, which has been loss-making and is about to merge its container operations with Heung-A, sold 11 ships for breaking on the beaches in 2018: eight vessels ended up in Bangladesh and three in India, where in April, during the demolition of Sinokor’s PLATA GLORY at Leela Ship Recycling Yard [1], a worker died hit by a falling iron plate.

Norwegian Nordic American Tankers (NAT) - incorporated in Bermuda and stock-listed in New York - is runner-up for the ‘worst dumper’ prize. Last year, NAT reported having earned USD 80 million for the sale of eight vessels for breaking. Three were sold to Alang for breaking and five were sold to breakers in Chittagong. According to local sources in Bangladesh, the cutting operations of these ships started without required government authorisations. The sale of two additional vessels to yards in Bangladesh with particularly poor track records and where two workers were killed in 2018, prompted Norwegian pension fund KLP to blacklist the company.

Seven vessels were sold to beaching yards for dirty and dangerous scrapping by German owner Dr Peters GmbH & Co KG. According to local sources, fitter Md Samiul lost his life while scrapping Dr Peters’ DS WARRIOR in December 2018.

Other known shipping companies that in 2018 sold their vessels for the highest price to the worst breaking yards include: Chevron, Costamare, H-Line, Louis plc, Seabulk, SOVCOMFLOT, Teekay, Zodiac Group and CMB. Belgian CMB is still under investigation for the export of the MINERAL WATER to Bangladesh in 2016.

With the oil and gas sector seeing a downturn in the last couple of years, the Platform has documented an increase in offshore units that have gone for scrap. Out of the 138 oil and gas units which have been identified as demolished in 2018 alone, 96 ended up on the beaches of South Asia. Figures include 81 small-sized tug/supply ships and 33 semi-submersible platforms. Noble Corp, ENSCO, Tidewater, Diamond Offshore and Petrobras are amongst the biggest offshore players that dump their assets on the South Asian beaches. While most assets were exported from either East Asia or America, Diamond Offshore and cash buyer GMS are under investigation in Scotland for having attempted to illegally export three platforms that had operated in the North Sea and were cold-stacked in Cromarty Firth. The platforms have been under arrest in Scotland since January 2018.

Ship owners are facing increased pressure from investors and credit providers to stop selling their ships to beaching yards. In early 2018, Scandinavian pension funds KLP and GPFG were the first to divest from four shipping companies due to their beaching practices. Today, banks, pension funds and other financial institutions are actively taking a closer look at how they might contribute to a shift towards better ship recycling practices off the beach, taking into account social and environmental criteria, not just financial returns, when selecting asset values or clients.

Losing financing and clients, however, should not be the only concern of ship owners who continue to use dirty and dangerous scrap yards. In 2018, and for the first time ever, a ship owner was held criminally liable for having illegally traded four end-of-life ships to Indian beaching yards. Several other cases of illegal traffic are under investigation. These cases focus not only on the liability of the ship owner, but also on the responsibility of insurers, brokers and maritime warranty surveyors. By unravelling the murky practices of shipbreaking, which involve the use of middle men, or cash buyers, and flags of convenience such as Comoros, Palau and St. Kitts & Nevis, these cases highlight the importance of conducting due diligence when choosing business partners.

For the list of all ships dismantled worldwide in 2018, click here. *

For detailed figures and analysis on ships dismantled in 2018, click here.*

* The data gathered by the NGO Shipbreaking Platform is sourced from different outlets and stakeholders, and is cross-checked whenever possible. The data upon which this information is based is correct to the best of the Platform’s knowledge, and the Platform takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the information provided. The Platform will correct or complete data if any inaccuracy is signaled. All data which has been provided is publicly available and does not reveal any confidential business information.

NOTES

[1] The Plata Glory was beached in December 2017 at Leela Ship Recycling yard. Leela holds a so-called Statement of Compliance with the Hong Kong Convention issued by ClassNK and claims to be offering “green recycling”.

[2] The EU has published a list of ship recycling facilities around the world that comply with high standards for environmental protection and workers’ safety. The EU list of approved ship recycling facilities is the first of its kind and an important reference point for sustainable ship recycling.