Due to the annual monsoon season, activities remained slow at the South Asian shipbreaking yards over the summer months. However, when the breaking took up again in September, one worker, Ashok Yadav, was reported killed whilst at work at shipbreaking plot no. 14 in Alang, India. Following his death, a letter denouncing the unsafe working conditions at the shipbreaking yards in Alang was sent to Indian Government officials by Toxics Watch Alliance. Around the same time, Md. Shohag – 21 years old – was seriously hurt while torch-cutting a vessel at Zuma Enterprise in Chittagong, Bangladesh, when an iron plate hit him on the left foot and stomach, causing severe injury.

It is not due to a lack of awareness concerning the dire working conditions that ship owners continue to favour the infamous beaching yards in South Asia. Rather, it is the fact that dirty and dangerous breaking brings in more money, as there is (1) little or no investments in proper infrastructure to contain pollutants and ensure safe working conditions; (2) the proper disposal of hazardous wastes is overlooked; and (3) migrant workers are exploited.

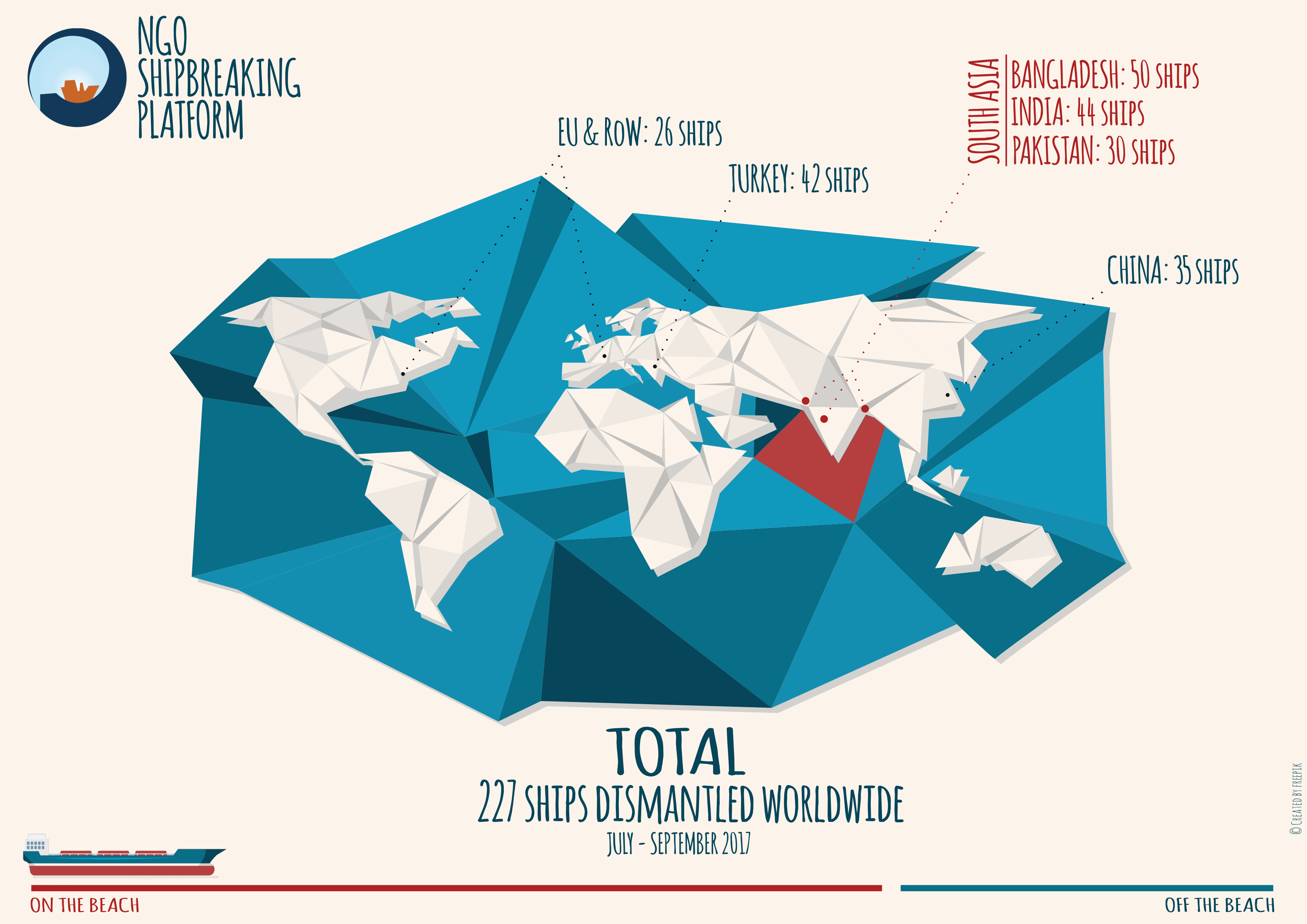

Moreover, the prices offered for ships this third quarter have been high in South Asia, especially when compared to the figures of the first half of the year. Monsoon rains caused a shortage of local product being available to the domestic steel mills and have, therefore, driven prices for end-of-life ships up. Whilst a South Asian beaching yard can pay about USD 400/LDT, Turkish yards are currently paying slightly less than the USD 250/LDT offered by Chinese yards.

Greek ship owners have, unsurprisingly, sold the most ships to the beaching yards with 11 beached vessels this quarter, followed by South Korea and Singapore with 6 vessels each. Shipping companies from the United States sold 5 vessels. Singaporean Continental Shipping Line remains the worst corporate dumper, though it currently shares this position with the Greek Anangel Shipping Enterprises and the Iranian Iran Shipping Lines. In total, these companies had three vessels each beached in South Asia in this quarter. Bermuda-based Berge Bulk, Greek Costamare, Swedish Holy House Shipping, and American SEACOR are close runner-up’s, with two ships each sold for dirty and dangerous scrapping on the beach. Brazilian-owned product tanker LOBATO, which was reportedly sold by Petrobras to Indian breakers, ended up on the muddy shores of Chittagong instead. Notably, no tanker was sold to the Gadani yards in Pakistan following the ban on tankers due to the major explosion on the ship ACES on the 1st of November of last year.

Although 33 out of the 124 beached vessels this quarter were European-controlled, only three of these had a European flag when they arrived on the beach. All ships sold to the beaching yards pass via the hands of scrap-dealers, also known as cash-buyers, that often re-register and re-flag the vessel on its last voyage. In this regard, flags of convenience, in particular those that are grey- and black-listed under the Paris MOU, are used by cash-buyers to send ships to the worst breaking locations. Almost half of the ships sold to South Asia this quarter changed flag to the grey- and black-listed registries of Comoros, Niue, Palau, St. Kitts & Nevis, and Togo just weeks before hitting the beach. These flags are not typically used during the operational life of ships and offer ‘last voyage registration’ discounts. Importantly, they are grey- and black-listed due to their poor implementation of international maritime law.

Efforts to counter the shipping industry’s crave for cash at the detriment of workers and the environment in South Asia are being brought to the attention of enforcement authorities and Courts. In Bangladesh, the Platform has been successful in taking legal action to halt the breaking of the FPSO North Sea Producer, which was illegally exported from the UK in 2016. Moreover, German authorities have been asked by the Platform to hold ACL, a subsidiary of Italian Grimaldi Group, liable for the illegal export of two ships, the Cartier and the Conveyor, to India.